Part 3

Müller’s “Experiences” at the Main Camp Crematorium

by Carlo Mattogno

Müller’s “Experience” at the Birkenau “Sonderkommando”

Transfer to Birkenau, and Assignment to the “Sonderkommando” In the two declarations of 1946 and 1947, as noted earlier, Müller limited the description of his experiences almost exclusively to the Main Camp’s crematorium. At that time, he knew only trivial anecdotes bandied about by the resistance about Birkenau. Only many years later did he elaborate on his “experience” at Birkenau, which became predominant since the Frankfurt Trial.

In 1946, he stated:

“Finally, when we had sprinkled the corpses with chlorine and earth, they took us back to the camp where we were again put in the dark cell which we had occupied up to August, 1943. We worked at the crematorium from morn till night” (Kraus-Kulka Statement),

which is to say that he remained in Auschwitz until his actual transfer to Birkenau.

During the Frankfurt Trial, the witness gave a completely different version:

“Witness Filip Müller: There are inmates standing at the gates, a labor service, and they say: ‘Take the inmates to the camp!’ Yes, that was already at the end of my stay there. And he takes us to the camp. The labor service comes to me and says to me: ‘You, if you bring me a lot of dollars ‘– a lot, yes, he doesn’t say how many – ‘[I’ll get you out] of there.’ And I did it.

Presiding Judge: What did you bring him?

Witness Filip Müller: I brought him a large, such a package of American dollars, to the inmate.

Presiding Judge: Yes.

Witness Filip Müller:

That was in the morning. When we got back, I give it to him, and he says to me, ‘Stay here.’ And where the kitchen was, there was a block on the other side, and he says to me, ‘Here, stay in the washroom.’ I stay there, he comes and he puts me up in Block 14. And I worked in Block 14. Later, I was transported to Buna, Monowitz.” (97th hearing, Oct. 5, 1964, Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20507f.)

These events sound blatantly unlikely and false. It must be remembered that Müller was assigned to the “Fischl-Kommando” of the crematorium, which had seven inmates and which later became the “crematorium working party” under the command of Kapo Mietek Morawa (Müller 1979b, pp. 39f.), which was controlled by Stark. How can one seriously believe that Müller could leave this Kommando so easily, especially since in the meantime he had become a “carrier of secrets”?[33]

Moreover, since the people allegedly gassed evidently were Jews from Polish ghettos, how can one seriously believe that their pockets were full of US dollars? While it is true that US dollars were a coveted currency in Eastern-Bloc countries during the Cold War – that’s where Müller lived when he testified in Frankfurt – US dollars were pretty much useless in Europe prior to and during the war.

After his transfer to Monowitz, which took place at the end of June 1942, Müller remained “in Monowitz until the spring of 1943” (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20508f.”), that is, for at least 9-10 months; he recounted the subsequent events thus:

“And I get a big phlegmon. I couldn’t work [anymore], in the infirmary I was afraid [of] what was there. And once an Unterscharführer sees us. There were three more of us. One had, I think it was typhus. He had a fever. And we don’t work. So we are hiding. He sees us, [takes] us out, and the next evening we came to Birkenau together with 30 other inmates.” (Ibid., pp. 20509f.)

Although, as he pointed out, he was sent “from Buna to Birkenau as a ‘Muselmann’” (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20510), instead of being gassed for being a “Muselmann” (a term used for an emaciated inmate with no hope of recovery), he was hospitalized at the infirmary, was treated, then went through a convalescent block (Schonungsblock; ibid., p. 20511) and ended up in a Kommando of potato peelers (Kartoffelschälkommando), where he remained for approximately 3 months.

At the 97th and 98th hearings of the Frankfurt Trial, Müller stated that he was transferred to Birkenau in the early summer (Sommerbeginn) of 1943, joined the “Sonderkommando,” and was housed in Block 13 (ibid., pp. 20759-61). At first, he was assigned to Crematorium. I [= II], where he spent “about five or six weeks” , then was transferred to Crematorium IV [= V], which also happened in the summer of 1943 (ibid., pp. 20523f.). The Main Camp’s Crematorium Kommando (Fischl-Kommando) followed him “14 days or a month” later (ibid., p. 20760).

In his statement to Kraus-Kulka, Müller stated that the transfer was due to the fact that he had refused the appointment to Kapo (=foreman). This position had been offered to him because his “prison [=inmate registration] number was lower than those of all the others working” at the crematorium, therefore he had been an inmate for the longest time. Keep in mind, however, that Müller’s registration number was 29236, while that of his friend Jankowski was 27675, hence Jankowski had arrived at Auschwitz earlier than Müller.

In his book, Müller took up the first version: he returned to Birkenau 15 months after he had first stayed there for a few days; the “Sonderkommando” of the Auschwitz crematorium was transferred to Block 13 of Birkenau Sector BIId (Müller 1979b, p. 52), after about 14 months of isolation in Block 11 of the Main Camp (ibid., p. 53). In reality, at Birkenau he was sent directly to the “crematorium team” (ibid., p. 57). The 15 months mentioned above refer to July 1943, the month explicitly indicated by the witness as that of the closure of the old crematorium at the Main Camp, to be precise “mid-July 1943” (ibid., p. 51). This date (like many other data that I will point out in turn) is taken from Jankowski ‘s statement:[34]

“I, along with the entire commando of stokers, six Jews and two Poles in number, was transferred to Birkenau in July 1943 and assigned to Crematorium V.”

Müller therefore went to Birkenau with the entire Kommando of the crematorium, but in Frankfurt he had stated that this Kommando had arrived there “14 days or a month” later.

In further contradiction to this, he wrote that “a few days later” – after his arrival at Crematorium II – he was transferred together with the Kommando Lemke, of which he was a part, to Crematorium III (Müller 1979b, p. 65). This therefore evidently happened around mid-July 1943. A few pages later we find him a stoker in Crematorium V, without him saying when he was sent there. Here is the relevant passage (ibid., p. 68):

“For some weeks now I had been a stoker in crematorium 5. During this particular night we cremated corpses from a transport from France [German edition: “from Malines in France”; 1979a, p. 108].”

In the summer of 1943, only three transports were directed to Auschwitz from the Malines Camp, which was located in Belgium, not in France. Transport No. XXI arrived there on August 2, while Nos. XXIIa and XXIIb both arrived there on September 22. From the first, 1,087 deportees were allegedly gassed, from the other two, 875 deportees.[35]

The next morning, Müller says, another 2,000 Jews arrived in the courtyard of Crematorium V (Müller 1979b, p. 69). This figure of 2,000 deportees is compatible only with the date of August 3, the day when several transports from the Będzin and Sosnowice ghettos are said to have arrived at Auschwitz (according to Czech, four transports with altogether 9,000 deportees as well as a smaller one with 200 deportees from Berlin arrived on August 3; Czech 1990, p. 454).

But if Müller had started working at Crematorium II in mid-July, and a few days later had been sent to Crematorium III, only to have been working at Crematorium V already for a few weeks in early August, how could he then have seen, “toward the end of the summer of 1943” (hence probably September 1943) the establishment of a “workshop for melting gold” at Crematorium III, as he claims (Müller 1979b, p. 68)?

From Crematorium V, Müller was inexplicably sent back to Crematorium II:

“One evening at the end of October 1943, I moved out to Crematorium II with a squad of about 100 prisoners on the night shift.” (Müller 1979a, p. 129)

The English translation of Müller’s book omits to mention any crematorium, thus sanitizing Müller’s tale of this inconsistency:

“One evening towards the end of October I went on night duty as one of a team of 100 prisoners.” (1979b, p. 81)

The first documented data on the strength of the crematorium staff (Krematoriumspersonal) dates to January 15, 1944 and mentions 383 inmates for the four crematoria of Birkenau. It is therefore extremely unlikely that three months earlier Crematorium II alone had a night shift of 100 inmates, all the more-so since not even from an orthodox point of view there was any need for night-time activities due to a lack of gassings during these months.[36]

But Müller’s transmigratory vicissitudes do not end there. During the alleged gassing of the inmates of the Theresienstadt Family Camp on March 8, 1944, which involved 3,700 people and began in Crematorium II according to Müller (1979b, pp. 106f.), he was on the spot by a lucky coincidence and managed to witness it all (ibid., p. 107):

“Together with about thirty prisoners I was in the underground passage which linked the changing room to the gas chamber.”

Then when the second part of the victims was taken to Crematorium III, Müller saw the car of the “disinfecting operators” enter the courtyard of Crematorium III, meaning that the next batch of victims would be disposed of there (ibid., p. 116).

According to the orthodox version later sanctioned by Danuta Czech, the inmates of the Family Camp were indeed gassed in Crematoria II and III (Czech 1990, p. 595).

Müller’s transmigrations are therefore clearly a mere literary device invented by him in order to be credited as an “eyewitness” of all the most-important events in the fables of Auschwitz. And in fact, at the beginning of May 1944 he was back at Crematorium V to participate in the excavation of the alleged cremation pits! (Müller 1979b, pp. 126f., 129-132)

The Selections of the “Sonderkommando"

If we credit the orthodox post-war narrative, the inmates of the “Sonderkommando” were dangerous “carriers of secrets” (Geheimnisträger) who had to be eliminated periodically, generally every three or four months.[37] By the early 1960s, this alleged procedure was considered an established fact. For this reason, this controversial dialogue took place at the Frankfurt trial (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20572f.):

“Presiding Judge: Yes, it was always said that the members of the ‘Sonderkommando’ who had been there for three or four months, who knew so much and who had seen so much, were then always killed, so that they would stay there any longer.

Witness Filip Müller: No.

Presiding Judge: So we’ve been told so far.

Witness Filip Müller: [+[38] There] were selections, but you couldn’t say every two or three months.”

Considering the fact that Müller remained a member of the “Sonderkommando” until January 1945 according to his own narrative, he is evidently unable to explain his beyond-miraculous survival of at least seven selections – assuming that they occurred every four months until November 1944, when all homicidal-gassing activities are said to have been stopped (Müller 1979b, p. 161). Hence, he was forced to disavow the dogma of the periodic extermination of the “Sonderkommando,” thus leaving the judges baffled.

But the problem came back in another form. Müller wrote that, at the end of Birkenau’s alleged extermination activity, “all traces of the summer’s mass exterminations” were to be erased and that the number of the “Sonderkommando” inmates were reduced to 200 (ibid., p. 160). Of these, 100 were saved, which were divided as follows: 70 were part of the demolition team, the remaining 30, including Müller, worked until January 1945 in Crematorium V (ibid., p. 161). Therefore, the SS of Auschwitz set out to cover up the traces of the alleged exterminations, but left 100 “eyewitnesses” of them alive! Müller could not ignore this irremediable contradiction, which all self-proclaimed witness veterans of the “Sonderkommando” run into. Not knowing how to handle it, however, he appealed to the SS’s mysterious ways of doing things (1979a, p. 271):

“Again and again I asked myself how it came about that we, the remaining carriers of secrets of the Sonderkommando, had not been shot before the evacuation. I couldn’t find a reasonable answer to this question.”

The English translations condensed this down considerably (1979b, p. 166):

“Again and again I asked myself why we, the last few remaining Sonderkommando prisoners, had not been shot before the evacuation.”

On the other hand, 5 “carriers of secrets” of the “Sonderkommando,” Müller’s colleagues – Waclaw Lipka, Mieczyslaw Morawa, Joseph Ilczuk, Wladyslaw Biskup and Jan Agrestowski – were transferred from Birkenau to Mauthausen on January 5, 1945, allegedly in order to be killed there,[39] which is an unfounded and utterly absurd claim, because it implies that these inmates were transferred from a death camp to a mere concentration camp a long distance away in order to be killed there!

But there is an even-more-striking contradiction that demands a reasonable explanation. In 1946, Müller had stated:

“I am the oldest member of the Auschwitz and Birkenau Sonderkommando and the only one [jediný] to have been through everything [který všechno přežil: who survived everything]. I only escaped death as a result of a number of lucky chances; it was indeed a miracle.” (Kraus-Kulka Statement)

This claim of the immediate postwar period was typical and indicative both for these witnesses’ arrogance and vanity. For instance, Miklós Nyiszli claimed to have been the only surviving “Sonderkommando” physician, and so did Dr. Charles Sigismund Bendel (Mattogno 2020a, p. 332). Then there is the only survivor of the “Sonderkommando” allegedly gassed on December 5, 1942 – Arnošt Rosin – and at the same time the other only survivor of this gassing, a certain Spanik (Mattogno 2021, pp. 333).

Hence, without giving any explanation, Müller transmogrified from the only survivor to one among one hundred only survivors!

In his book, Müller wrote that he had survived “one Sonderkommando selection after another” (Müller 1979b, p. 166) but previously stated that he had only experienced three selections (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20572):

“In the years 1943 to 45, there were selections in Birkenau. But I say there weren’t any in the main crematorium, in the main camp.”

“In 1942, when I was working in the Auschwitz crematorium, there was absolutely no selection. […] In 1943 there was one selection.” (Ibid., p. 20573)

“In 1944 there were practically two selections.” (Ibid., p. 20657)

Regarding the first selection, Müller stated (ibid. pp. 20573f.):

“In 1943 there was one selection. That was at the end of the summer of 1943, when the selection was made, in the courtyard of Block 13. We were 30 prisoners as stokers. We worked in Crematorium IV. [= V…]

Then we came back and there was already a selection. Schwarzhuber was there. And the strong ones were taken; they were told: ‘You are going to Lublin.’ And those who were not strong were left there, so that … But afterwards, when the ‘Sonderkommando’ comes from Lublin, we see that they have boty, holínky.

Interpreter Stegmann: Shoes, boots.

Presiding Judge: From your people who went into the gas there.

Witness Filip Müller:

"We ask them; they say they were gassed there. That was one [the first]. The second time was again a selection.”

The Auschwitz Museum’s story line has nothing about a selection among “Sonderkommando” members at the end of summer 1943. Müller, who here relied heavily on rumors, had the misfortune of speaking about it before Danuta Czech cast the narrative of this event into its final shape, which she did only in 1989, when she dated that event to February 24, 1944 (Czech 1989, p. 728/1990, p. 588). The previous German edition of her Kalendarium, which appeared in 1964, did not mention it at all (Czech 1964a, p. 80).

Picking up this legend, Franciszek Piper subsequently developed it as follows, also thanks to Müller’s imaginative tale: on February 24, 1944, all the members of the “Sonderkommando” were gathered in the courtyard of Block 13; the Lagerführer called out the registration numbers of a group of inmates, who were then transferred to the Majdanek Camp (Piper 2000, p. 185):

“They were killed shortly afterwards. […] Those who remained behind in Auschwitz learned about the fate of their colleagues in April. Nineteen Soviet POWs arrived in Auschwitz then; they had worked at the Majdanek crematorium and had witnessed the executions of the former Auschwitz Sonderkommando members.”

From this it follows that these Auschwitz inmates were killed in the Majdanek crematorium, but according to the Majdanek museum’s current narrative, there was no gas chamber in that building (Kranz, pp. 219-227; for Müller they were gassed). The only claimed gas chambers are said to have been located at the opposite end of the camp, in Building XIIA, but the orthodox narrative has it that they ceased their homicidal activity in early September 1943, and on September 21, the 23 detainees who had worked there were allegedly shot (ibid., p. 226). Piper ‘s claims are therefore as unsustainable as Müller’s.

Jankowski also told the story of the 200 inmates of the “Sonderkommando” who had been transferred to Majdanek, and also elaborated on a transport from this camp to Auschwitz, to which Piper alluded:[40]

“At the beginning of 1944, a transport arrived at the Birkenau Camp from Majdanek containing 300 Polish Jewesses, 19 Soviet prisoners and a German inmate who had been Kapo in Majdanek. The men were placed in Block No. 13, in the Sonderkommando, being assigned to work in the crematorium. The 300 women, on the other hand, were kept for 3 days in the Sauna, that is, in the bathhouse, then they were taken to the crematorium, where during the night they were shot and cremated. I know of the shooting and cremation directly from my comrades from the Sonderkommando, who were on duty that night and were eyewitnesses to the execution, and then took part in the cremation of the corpses. The entire transport of Jews executed at the camp was obviously not recorded anywhere.”

His two colleagues, Dragon and Tauber, didn’t have much better information than he did either. Dragon declared:[41]

“Mostly Slovaks worked in the Sonderkommando that worked at the two bunkers before my assignment to the new Sonderkommando established in December 1942. As I stated earlier, the Sonderkommando to which I was assigned consisted of 200 inmates. Within a short period of time, it was increased to 400. Later, 200 inmates of this Sonderkommando were transferred to Lublin, from where 20 Russians arrived at the Sonderkommando. From these Russians, we learned that these 200 inmates transferred to Lublin had been shot there. In 1943, 200 Greeks were assigned to our Sonderkommando, and in 1944 500 Greeks.”

He didn’t make any specific statements about the dating of this claimed event. Tauber roughly dated the event, but asserted that 300, not 200, inmates were transferred:[42]

“At the beginning, when I was assigned to work in the Sonderkommando, it had about 400 inmates and maintained this force until January or February 1944. In one of these months a transport of about 300 inmates was sent to Lublin. […] After this transport was sent to Lublin, about 100 remained. From Lublin, 20 Russians and the German Kapo Karol were sent and assigned to our group.”

Also in this case it is worth highlighting the irreducible stupidity that witnesses (and orthodox Holocaust historians) are forced to attribute to the SS to support their legends: the 200 inmates in question were sent to die in the Majdanek crematorium so that their comrades of the Auschwitz “Sonderkommando” would not know anything about it, and at the same time they transferred 19 or 20 Soviet PoWs to this “Sonderkommando” who “had worked at the Majdanek crematorium and had witnessed the executions of the former Auschwitz Sonderkommando members,” evidently informed as to all details of the alleged execution!

Danuta Czech states that the transport from Majdanek arrived at Auschwitz on April 16, 1944, and contained 299 Jews with 2 infants and also 19 Russian PoWs who were assigned to the “Sonderkommando” (Czech 1990, p. 612).

Returning to Müller, being unable to plagiarize a story at least already sketched out, he was forced to improvise, and he did it badly. The related choppy, almost unintelligible dialogue during the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial shows that he did not know what to say and was inventing things on the fly; he got himself into trouble, claiming that there had been a selection among the “Sonderkommando” of Crematorium IV (= V), but it did not involve the 30 stokers who were part of the “Sonderkommando”. Hence the questions of the President Judge (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20574-20576):

“Presiding Judge: Who were the prisoners in ‘Sonderkommando’ 13 who were not on duty in the crematorium? What kind of work did they have or what kind of task did they have?

Witness Filip Müller: They were room attendants who were not in the crematorium.

Presiding Judge: And yet [they] were in the ‘Sonderkommando’?

Witness Filip Müller: Yes.

Presiding Judge: Who therefore were always selected there, as you just said?

Witness Filip Müller: Yes.

Presiding Judge: They were all room attendants?

Witness Filip Müller: No, those were only inmates who worked in the ‘Sonderkommando’.

Presiding Judge: And what were they doing in the ‘Sonderkommando’?

Witness Filip Müller: Working.

Presiding Judge: Exactly the same thing you were doing?

Witness Filip Müller: They weren’t stokers, but something else.

Presiding Judge: But what were they?

Witness Filip Müller: They have the clothes …

Presiding Judge: You said earlier that there was not a division [of labor]; that one person did this, the other that, but everyone who was in the ‘Sonderkommando’ was also used for everything.

Witness Filip Müller: Yes, yes, yes. That’s the way it is.

Presiding Judge: And how come these people who were selected before you were already in your Block 13?

Witness Filip Müller: Well. We were there as stokers. But Gorges came many times and said: ‘The clothes you have to’…

Presiding Judge [interrupts]: Take away.

Witness Filip Müller: That happened, too, yes. It wasn’t always so. It was not divided [so] that [it was said]: ‘This one has [to do] this’ or ‘That one there has [to do] that’. But we always came into the camp after the roll call.”

With these awkward and confused statements, the witness tried painfully to get out of the embarrassing situation he found himself in: the “selection” had taken place (and thus saved face), but it had not concerned the actual members of the “Sonderkommando,” but rather elements somehow associated with it (and so he explained why Holocaust historiography knew nothing of that “selection”).

In his book, this “selection” disappears, or rather, it is transformed into that of February 24, 1944 mentioned earlier. In the related description that follows, Müller was inspired by the stories of Chaim Herman and Salmen Lewental which had appeared in a German edition in 1972:[43]

“In February 1944 there was a selection among members of the Sonderkommando. One evening during roll-call Lagerführer Schwarzhuber, Rapportführer Polotschek and another few SS men appeared in the yard of Block 13. From among the prisoners they selected about 200, telling them that they would be transferred to Lublin where strong men were needed for a special job. Most of them belonged to the group which, with Hössler in charge, had taken part in removing all traces of the mass graves near bunkers 1 and 2. Since work there had come to an end, they were now expendable.” (Müller 1979b, p. 90)

However, the motivation for the alleged selection is senseless from an orthodox point of view, given that, as Piper informs us,

“when the new gas chambers and crematoria entered operation in the spring of 1943, use of the two ‘bunkers’ ceased. Bunker 1 and the adjacent barracks were demolished and the burning pits filled in and levelled. The same was done with Bunker 2, except that the ‘bunker’ itself was not demolished.” (2000, p. 143)

Therefore, the elimination of these mass graves had taken place in early 1943, which means that the inmates who had worked there would have been “useless” ever since; but then why did the SS wait until February 1944 to carry out the “selection”?

It is clear that Müller had no knowledge of these alleged events and invented everything badly.

Shifting the claimed selection from 1943 to 1944 meant that, for this year, he found himself with three selections, while at the Auschwitz trial he had spoken of only two for 1944.

The second selection of 1944 took place, according to the witness, “a few weeks before the revolt” of October 7, in the course of which “several hundreds” of prisoners were killed (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20647, 20706).

In his book, he sets it “towards the end of September 1944” in Crematorium IV (Müller 1979b, p. 152).

Piper claims that the alleged selection was “at the end of September,” but his only source is Müller’s book! (Piper 2000, Note 563, p. 186) A wise decision, because Dragon and Tauber had made conflicting statements about it. For Dragon, the presumed selection took place after the revolt of October 7, 1944, for Tauber (who traced the revolt to September), before the revolt. Dragon:[44]

“In October 1944, 500 inmates were shot, in particular 400 in the courtyard of Crematorium No. IV and 100 in the camp sector near Crematorium No. II. This same month, Moll selected about 200 inmates from the Sonderkommando, who were taken to Auschwitz and, as we were later informed by the inmates employed at Kanada, were gassed in the chamber that was used to fumigate the items in the Kanada warehouse.”

Tauber:[45]

“We set the date of the revolt to June 1944. I don’t remember the exact date. The revolt, however, did not happen, although everything was ready for its outbreak, and even people from whom we had hidden the preparation of the revolt participated in the secret action. This affair did us a lot of damage, and after it was discovered, it resulted in many victims. First our Kapo Kamiński was shot shortly after the deadline set for the revolt. Since then we were transferred to Crematorium IV to make any contact with the world impossible. About 200 inmates were selected and sent into the gas. They were gassed in the delousing [facility] of the ‘Kanada’ [camp warehouse section] in Auschwitz, and cremated in Crematorium II. This cremation was carried out by the SS themselves who were assigned to the crematorium. The situation became more and more serious for us, and although we were monitored and examined with doubled vigilance, we decided to flee from the camp at any cost. After the preparations, there was a revolt in Crematorium IV in September 1944; it also involved Crematorium II.”

As Piper points out correctly, the series of labor-deployment reports of the Birkenau men’s camp records a decrease in strength of the “stokers Crematorium (I-IV)” from 874 inmates on September 7, 1944 to 662 of October 3,[46] but the reports in between have not been preserved, and it is not known when or why this decrease occurred. It is clear that neither Müller nor Piper can back up their claims with anything.

Müller’s third selection allegedly took place on an unspecified date, but in any case after the revolt of October 7. Müller spoke of it like this:

“In the year 1944, that was already towards autumn, back then the commando leader was already Scharführer Buch. At that time, Moll was already gone. It so happened that Buch made a selection. He selected and said: ‘There are 300 inmates here in Crematorium III, IV. Of these 300 inmates, 270 will go to a very good job. And they’ll have a great time, bread, drinks, everything.’” (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20557f.)

In practice, according to his deposition at the Frankfurt Trial, only the 30 inmates housed in Crematorium V were saved, the other 270 were shot.

In further contradiction to himself, Müller reported in his book that, after the revolt of October 7, the “Sonderkommando” was reduced to 200 prisoners rather than 300 (Müller 1979b, p. 160). About 450 prisoners were killed in the “Sonderkommando” revolt (ibid.), which he cribbed from the first German edition of the Kalendarium of Auschwitz, where Czech mentions precisely the decrease in force from 663 to 212 inmates (Czech 1964a, pp. 73, 75), so that the number of those allegedly killed was 451. The survivors were finally 100 inmates, the aforementioned 30 plus another 70, who were assigned to the demolition team (Müller 1979b, p. 161).

The origin of these two figures is revealing. Müller drew the first from Nyiszli, although Nyiszli had explicitly stated that the 30 inmates he mentioned were not part of the “Sonderkommando”; the second number Müller took from Kraus and Schön/Kulka, for whom 70 was the total number of surviving inmates of the “Sonderkommando”! (See Subchapter 3.4.)

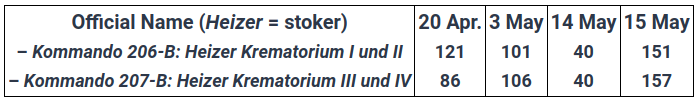

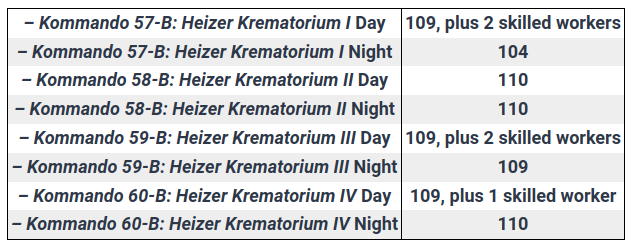

According to the documents, the official name of the so-called “Sonderkommando” was the following, with the number of inmates assigned to it in subsequent columns (which remained practically unchanged from July to the beginning of September 1944; see Mattogno 2016a, pp. 83-92):

April-May 1944:

Since July 1944:

During meetings and for other bureaucratic needs, the respective units were called by these names, but Müller clearly knew nothing of them.

3.3. Müller’s Miraculous Survival In Müller’s account of the “Sonderkommando” revolt of October 7, 1944, the only thing that stands out is how he survived the repercussions. Crematorium IV was set on fire, but he entered it anyway and took refuge in the building’s furnace room (Verbrennungsraum), which was ablaze:

“I was by now completely out of breath. The crematorium was still burning fiercely. The wooden doors were ablaze, several of the wooden beams were charred and dangling from the ceiling, and there was a fire raging in the coke store.” (1979b, p. 156)

And outside, a gun battle was raging.

“In a flash I remembered a place where I would be safe from bullets: inside the flue leading from the ovens to the chimney. I lifted one of the cast-iron covers, climbed down and closed the cover behind me. Inside the flue there was no room to stand upright; I stretched out trying to catch my breath. From outside I could still hear the rattle of machine-guns. When after a while the shooting seemed to die down I crawled towards the chimney because I was able to stand up there.” (Ibid.)

During the 97th hearing of the Frankfurt Trial, the witness stated (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20564f.):

“There was a flap made of […] metal, a metal lid […] a duct. […] which connected the chimney with the furnace. […] A duct. And then get into the duct and stay there. I can already see the chimney up in front of me, and black water flows and – […] Hot water, boiling water flowed down. […] The fire brigade was already there. And all this pours on me, I’m already all [wet] from the water, and that’s where I stay. After a three-quarter hour or an hour I can already hear revolvers shooting. I heard how they were shooting outside because there was the chimney.”

In both stories Müller mentions only one “duct” and only one chimney, although he himself wrote earlier in the description of Crematorium V (which is mirror-symmetrical to Crematorium IV; Müller 1979b, p. 95):

“The raging flames rushed into the open air through two underground conduits which connected the ovens with the massive chimneys.”

But the fundamental problem is another: were the smoke ducts of the furnaces of Crematorium IV and V equipped with inspection shafts in the first place? To understand the significance of the documents and photographs I adduce, it is necessary to first know how this system was structured. I summarize the detailed description that I presented in my specific study on the crematory furnaces of Auschwitz (Mattogno/Deana, Vol. I, pp. 283f.).

The Topf coke-fired 8-muffle furnace was made up of eight single-muffle furnaces as per Topf Drawing D58173 arranged in two groups of four furnaces; each group consisted of two pairs of furnaces opposing each other in such a way that they shared their rear walls and the central walls of the muffles in a manner already used in the Płaszów crematorium. The two furnace groups were connected to four gasifiers coupled in the same way and thus formed a single 8-muffle furnace, also called “Großraum-Einäscherungsofen,” literally “large-scale incineration furnace.”

The two ducts ran horizontally in opposite directions below the floor of the furnace hall and ended in a chimney that had a square cross-section of 0.8 m × 0.8 m and a height of 16.87 m. The chimneys had no draft enhancers.

That said, let’s look at the question of the presence of inspection manholes.

Document 1 in the Appendix shows my diagram of the 8-muffle furnace: the two smoke ducts are indicated by No. 7. In the plan of Crematorium IV/V No. 1678(r) of August 14, 1942, the smoke ducts are indicated with dashed lines. Document 2 shows the foundations of the two 4-muffle furnaces. The numbers I have placed on it indicate, as in the above scheme:

5: vertical smoke duct 6: masonry containing the smoke ducts 7: horizontal smoke duct Achtmuffel-Einäscherungsofen: 8-muffle cremation furnace Schornstein: Chimney. M1-M8: the eight muffles (the squares represent the muffle openings).

Each of the two smoke ducts, which had to be at least as wide as the chimneys (0.8 m), was about 1.5 meters long from the external wall of the furnace to the chimney. This was the space available on the floor of the furnace room where an inspection manhole might be placed. The smoke ducts obviously crossed the external wall of the chimney, so that, up to the chimney flue, they were about 1.8 meters long. Any inspection manhole placed between the furnace and the chimney, which should have measured 0.45 m × 0.50 m,[47] would have been no more than one meter away from the chimney flue.

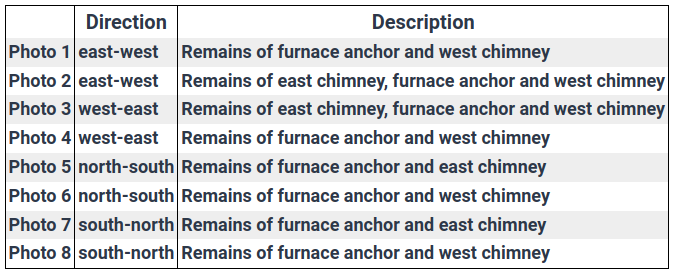

The detailed cost estimates and parts list of the Topf 8-muffle furnace (dated November 16, 1942 and September 8, 1942, respectively) contain no references to any manhole covers.[48] All that remains is to examine are the ruins of Crematoria IV and V. It should be noted that there is practically nothing left of Crematorium IV, while in Crematorium V the remains of the anchor rods of the 8-muffle furnace and the chimneys are still clearly visible. The two crematoria were built on the basis of an identical plan, but in mirror images. Hence, what is true for Crematorium V also applies to Crematorium IV.

When I visited the Birkenau Camp in 1997, having Müller’s story in mind, I made a thorough inspection of the ruins of Crematorium V in search of the inspection manholes of the smoke ducts, with negative results: they do not exist. On that occasion I took several photographs, of which I present the most-significant in the Appendix:

In the space between the furnace and the west chimney on one side and the east chimney on the other, there should have been an inspection manhole similar to those seen in Photo 9, relating to Crematorium III, equipped with a metal lid like the one that in 2010 was curiously located on the remains of the reinforced concrete roof of Morgue #1 of Crematorium II (Photo 10). But there is no trace of this in the ruins, so Müller’s tale is just another lie –shameless, but not an original one, because it was invented in 1945 by Szlama Dragon. In relation to the “Sonderkommando” revolt, this witness had in fact declared:[49]

“I hid under a pile of wood, and Tauber in the chimney flues [w ciągach komina] of Crematorium No. V.”

Henryk Tauber, on the other hand, did not confirm this fabrication.

Legendary Anecdote

In the Kraus-Kulka Statement, Müller related some of the many fabrications circulating in the immediate postwar period (see Part 3 in Mattogno 2021):

“Here I witnessed the ‘scientific’ experiments performed by SS doctors Fischer, Klein and Mengele. Between 100 and 150 men and women, aged from eighteen to thirty, were selected [from the transports] and shot – unlike the other prisoners who were gassed. A piece of flesh was then cut from their thighs and forwarded to the Bacteriological Institute at Rajsko [where bacteria were cultivated]. One of the SS, who was acting as assistant to an SS doctor, told me all about it, remarking that horse meat would have done just as well but would have been a waste.”

“Here,” as he explicitly said, was referring to Crematorium IV (=V). The following year, however, during the Krakow Trial, he stated:

“In the Auschwitz Camp, I also saw that the flesh of executed non-Jewish inmates was used for various purposes. These people were often shot in the presence of Dr. Mengele and others, whose names I do not know, and in the presence of Aumeier and Grabner. Immediately afterwards, the flesh from their calves was placed in crates, so that on average 6–8 crates of flesh were taken in a week.

It sometimes happened that a German commission came with swastikas on their arms, and asked in the presence of Aumeier and Grabner if it was human flesh. Aumeier replied: ‘Horse meat could also be used, but what a pity [to waste] horse meat!’”

From the context and the characters involved, it is clear that the scene was placed at the Main Camp’s crematorium.

Curiously, as if to take revenge for the plagiarism suffered, Jankowski in turn plagiarized the following imaginative story from Müller, embroidering it as follows (see Chapter 9):

“Every two weeks, SS doctors came to the undressing room and from the corpses cut off muscles, which were placed in clay pots with some disinfectant liquid. Muscles were cut from corpses, both of men and women, as long as they were shot and not gassed.”

Another fable related by Müller is this:

“The youngest women also served as a source of blood which would be drained from their veins for several minutes until they collapsed, after which they would be thrown half-dead into the fire. The blood was poured from a pail into special bottles which were then hermetically sealed. I was told that it was urgently needed at the military hospitals.” (Kraus-Kulka Statement)

To refute this nonsense, it suffices to give the floor to two former Auschwitz inmates, the famous Primo Levi and the less-well-known Leonardo de Benedetti, a Jewish doctor who, in 1946, wrote a “Report on the Hygienic-Sanitary Organization of the Monowitz Concentration Camp for Jews (Auschwitz, Upper Silesia),” in which, with reference to the camp hospital, we read among other things (Mattogno 2016, pp. 54-57, here p. 55):

“We shall cover such matters with the remark that even surgeries requiring a high surgical standard were performed, above all those involving penetration of the body wall such as gastroenteroanastomosis for duodenal ulcers, appendectomies, rib resectioning for emphysema, as well as orthopedic interventions for fractures and sprains. Where the overall condition of the patient did not assure that the trauma of the surgery could be withstood, the patient received a blood transfusion before initiating the procedure; transfusions were also performed to alleviate secondary anemia as well as severe hemorrhage from an ulcer or trauma sustained in an accident. For donors, recent arrivals to the camp were selected who were in good health; donation of blood was voluntary and was rewarded with 15 days’ stay in the hospital, during which time the donor receives a special diet, so that there was never any lack of volunteers for blood donation.”

There is also the pathetic rhetoric of the alleged victims who went to meet death with phenomenal pride and courage:

“I saw nationals of almost all the nations of Europe die in the gas chambers. Those from the Czech Jewish family camp were the only ones to go to their death singing their national anthem. [French female inmates sang the Marseillaise while on trucks riding to the gas chambers]” (Kraus-Kulka Statement)

The creators of this story forgot that the alleged victims were unaware of their impending fate, because the SS had set up a well-organized plot to deceive them – the pretense that they would take a shower and/or would be disinfested. It is therefore utterly unclear what would have motivated them to sing national anthems on the trucks.

In his book, Müller updated this fairy tale on the basis of the equally fabulous story by the “Unknown Author” which in the meantime he had been able to read in the pertinent book (Bezwińska/Czech 1972): Czechoslovakian Jews sang their national anthem and then “they sang ‘Hatikvah’, now the national anthem of the state of Israel” (Müller 1979b, p. 111).

Müller contributes to this anecdote by inventing a story – more pathetic than comical – to which he devotes almost four pages (ibid., pp. 111-114) that can be summed up in a few lines. He snuck into the gas chamber because he intended to die with the victims, but a group of girls intervened (ibid., p. 114):

“Before I could make an answer to her spirited speech, the girls took hold of me and dragged me protesting to the door of the gas chamber. There they gave me a last push which made me land bang in the middle of the group of SS men.”

If he really wanted to die, Müller could have thrown himself easily on the camp’s high-voltage fence: death would have been certain, without any last-minute savior.

Comments