Part 2

Müller’s “Experiences” at the Main Camp Crematorium

by Carlo Mattogno

Arrival and Duration of Stay at the Crematorium

First of all, it is necessary to establish the time limits of Müller’s stay in the crematorium, starting from the day he arrived there. In the Kraus-Kulka Statement, he claimed that he was assigned there on May 24, 1942. In the Frankfurt Statement (97th session) he declared that he arrived in Auschwitz on April 13, 1942 and was transferred to Birkenau the next day, where he remained for five to seven days. Later he said that he went to Birkenau on April 14 or 15, stayed there for three to four days and then was sent back to the Auschwitz Main Camp. After a couple of days, he was assigned to the “Buna Kommando” for eight to ten days, but in early May, he was sent back to Auschwitz, where he was assigned to the crematorium one Saturday.

Müller was quite sure it was a Saturday, because he explained that “the inmates always slept in on Saturdays, (there was an hour) or maybe more to sleep in.” (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20465)

It would therefore be the first Saturday of May 1942, which fell on May 2. This dating is in evident contrast with that of May 24, which was moreover a Sunday. Also in his book, Müller said that “It was a Sunday in May 1942” (Müller 1979b, p. 1), but he did not indicate the date. He remained at the Main Camp’s crematorium for about six weeks until the end of June 1942 (Fritz Bauer …, p. 20506):

“Witness Filip Müller: I was in the Auschwitz crematorium until about the end of June or the beginning of August [sic], I can’t, I can’t [remember] that.

Presiding Judge (interrupts): Well, roughly how many weeks was it?

Witness Filip Müller: Six weeks.

Presiding Judge: Six weeks.

Witness Filip Müller: About six weeks.”

This presupposes an arrival date around mid-May. The maximum period of the witness’s stay in the crematorium therefore runs from the beginning of May to the end of June of 1942.

The Crematorium’s Layout

How was the crematorium laid out at the time? The witness does not provide a description. As for the cremation’s appearance, he limits himself to mentioning the three double-muffle furnaces and the round chimney (“a round red-brick chimney,” Müller 1979b, p. 11). However, the “Inventory plan of Building No. 47a, BW 11. Crematorium” (“Bestandsplan des Gebäudes Nr. 47a. BW 11. Krematorium”) of April 10, 1942 shows in the blueprint a square chimney (see Mattogno/Deana, Vol. II, Docs. 206, 206a, pp. 349f.).

Müller then accurately describes the device for introducing corpses into the muffles (the “corpse-introduction device” – Leicheneinführungs-Vorrichtung, although he calls it “cast-iron truck”) and the “turn-table” (Drehscheibe; Müller 1979b, p. 14), which was used to turn the devices from a pair of rails running across the furnace room to one of the perpendicular sets leading to each muffle opening. Müller explicitly states that the system lacked an essential device – the pair of rollers (Laufrollen) onto which the side rails of the corpse-introduction stretcher were placed and which served to center the stretcher when it was pushed in, and to prevent it from dropping down onto the refractory grate prematurely, which could damage it. Müller mentions later, when talking about Crematorium II in Birkenau, that its furnaces had such rollers as the only “important innovation” (Müller 1979b, p. 59). Fact is, however, that the furnaces at the Main Camp’s crematorium were also equipped with these rollers. He probably claimed they didn’t exist, because the two furnaces on display in this building today were badly rebuilt by the museum right after the war, leaving out the rollers in the process, while the corpse-introduction device was mounted correctly (Mattogno/Deana, Vol. I, pp. 261f.). This suggests that Müller’s description in his book is not exclusively based on his memory (if at all), but at least to some degree on post-war observations.

After preheating the furnace, the corpses were placed in the muffles – three at a time (Müller 1979b, p. 15). In this regard, the witness states (ibid., p. 16):

“The powers that be had allocated twenty minutes for the cremation of three corpses. It was Stark ‘s duty to see to it that this time was strictly adhered to.”

He then adds that 54 corpses could be cremated in the three double-muffle furnaces within one hour, hence three corpses every 20 minutes in each muffle (ibid., p. 17). These claims put Müller’s tale squarely into the realm of fantasy, because the cremation capacity of the Auschwitz double-muffle furnaces was one corpse per hour and muffle, or six corpses per hour in the six muffles (Mattogno/Deana, Vol. I, pp. 251-265, 312-341). Therefore, Müller increased the actual furnace capacity by a factor of nine!

The Crematorium Fire and the Chimney’s Reconstruction

On the first day of the witness’s claimed activity at the crematorium, he was about to undress the corpses of the gassing victims, but then he was assigned to work on the actual cremations. In his first two statements, the related account is somewhat vague:

“Having had no previous experience of stoking furnaces, we bungled things badly. Fire broke out at the crematorium, which made it impossible for the corpses to be burnt.” (Kraus-Kulka Statement)

“Since we were being beaten without interruption and had no experience of running the crematorium facilities, we started a fire in the Auschwitz crematorium. As a result, the gassed victims could not be cremated.” (Krakow Statement)

This was the prelude to his alleged dispatch to a mass grave in Birkenau. At the Frankfurt Trial (97th session), Müller tried to formulate a somewhat-more-credible story. Together with another inmate, Maurice Lulus, he was first charged with removing the slag from the two furnaces’ gas-generator grates (“die Öfen entschlacken”), then these furnaces were fired up by Stark and an inmate named Fischl, and their operation was then entrusted to the inmates Müller and Lulus (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20475-78). Yet then, a fire broke out as follows (ibid., pp. 20478f.):

“And after that, after a few minutes, when the corpses were already burning, you had to turn on the fans – there were fans there too. And we couldn’t do that, we saw it for the first time.[7] And the fans, they were on too long, and that led to a fire in the crematorium.

Presiding Judge: A fire broke out.

Witness Filip Müller:

Yes, a fire. Because the fans [ran longer] than they were allowed to, and that’s why there was a fire. And then we have to extinguish it with water.”

In his book, Müller embroidered this story further (Müller 1979b, p. 14).

“Stark ordered the fans to be switched on. A button was pressed and they began to rotate. But as soon as Stark had checked that the fire was drawing well they were switched off again.”

This statement, which refers to the furnace’s preheating phase, is nonsense, technically speaking. Each of the crematorium’s three double-muffle furnaces was equipped with an air-induction device (Druckluftanlage) with a blower (Druckluftgebläse) driven by a 1.5-HP three-phase electric motor and associated ducts (Druckluftleitung), which entered the rear of the furnace and passed through its masonry above the two muffles. The supercharged air was ultimately fed through four openings placed in the apex of the muffle ceiling. The blower’s purpose was therefore not to stoke the fire in the gas generator, but to feed combustion air (oxygen) into the muffle, which was especially important in the cases of cremations using wooden coffins (which was not the case in Auschwitz). Therefore, if the blower had remained in operation for too long, it would only have cooled the refractory masonry of the muffles.[8]

How many furnaces were there? At the Auschwitz Trial (97th session), Müller stated that there were three furnaces with two muffles each, only one of which was fired up, although the terms he used to describe it were incorrect and confusing (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20477):

“Presiding Judge: So the furnaces were already on fire?

Witness Filip Müller: Yes, on fire, but only two.

Presiding Judge: Only two. And how many furnaces were there?

Witness Filip Müller: Six. […] Squares, these were three squares [= cuboids, blocks = furnaces]. In each square [furnace] there were two furnaces [muffles]. So six together.”

In 1979, he wrote (Müller 1979b, p. 14):

“Now all six ovens [muffles] were working.”

Müller then relates that the crematorium staff “had forgotten to switch off one set of fans,” which is inaccurate, because each furnace with two muffles had only one blower, and here’s what the claimed consequences were (ibid., p. 18):

“They had fanned the flames to such an extent that because of the intense heat the fire-bricks in the chimney had become loose and fallen into the duct connecting the oven to the chimney. This meant that the flames no longer had a way out; fiery red tongues were licking out of the oven and in no time the cremation room was enveloped in a dense fog of sickly choking smoke.”

This statement makes no sense either. As explained earlier, the purpose of the blower was not to stoke the fire in the gas generator, but to feed cold combustion air into the muffle. Had the blower been left on too long, the result would have been exactly the opposite of the witness claimed: the two muffles of the furnace would have cooled down to the point where the fire in the gas generator would have gotten weaker as well due to lack of draft, further decreasing the muffles’ temperature!

The “Operating Instructions for the Topf Coke-Fired Double-Muffle Cremation Furnace” (“Betriebsvorschrift des koksbeheizten Topf-Doppelmuffel-Einäscherungsofen”) prescribed for the heat-generating (second) phase of the burning of a corpse:[9]

“This increase in temperature can be prevented by blowing in air.”

This fire – continues Müller – was put out only in the evening; the crematorium had become unoperational.[10]

During the Auschwitz Trial, Müller provided further, no-less-fanciful explanations (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20578):

“Presiding Judge: Then you moreover told us that a fire had broken out in this Crematorium I in Auschwitz because you did not operate these ovens or the fans properly. What was actually burning there?

Witness Filip Müller: It didn’t burn like that. The fans tore out the bricks. And the fire came out.

Presiding Judge: Out of where, out of the ovens?

Witness Filip Müller: Torn out of the oven, yes. And then, with water, we had to

Presiding Judge (interrupts): extinguish.

Witness Filip Müller: But not a fire on the roof or something.”

This is another huge nonsense: the blowers operated at a very low pressure. By way of comparison, the three forced-draft devices originally planned for Birkenau Crematoria II & III operated with a pressure of 30 mm water column, with a 15-HP motor.[11] About the blowers for the double-muffle furnaces we only know that they had a much-lower flow rate, since they were driven by small, 1.5-HP motors.[12] But even 30 millimeters of water column equals just 0.3% of atmospheric pressure. How could such a small overpressure tear to pieces the furnace’s masonry (or that of the smoke ducts, if we follow his book’s narration)?

In his imaginative story, Müller adds more nonsense: from the alleged openings produced by the dislodged bricks, flames came out and caused the fire. This is the naïve conception of an ignoramus who thought that a cremation furnace acts like a barrel: if a hole were punched into it, the wine would flow out – or in this case the fire. If such nonsense were true, flames would have come out every time a muffle door was opened, and a fire would have started!

In reality, the gases in the muffles (cremation chambers) of a cremation furnaces always have a lower pressure than the outside air pressure due to the chimney’s draft, which increased with an increased temperature difference. It follows that a possible opening in the refractory masonry not only would not have caused flames to escape, but quite to the contrary, it would have caused large quantities of cold, outside air to rush into the furnace, cooling it down.

The witness confirmed to Lanzmann that there were “ventilators, which were used to heat up the fire,” which, as I have already explained, is false, and he added:

“So, we let them [the blowers] run for a longer time and suddenly, the firebricks caved in. And with that, the pipes of the Auschwitz crematorium to the chimney were blocked.” (Lanzmann 2010, pp. 8f.)

Müller stated that the fire had been extinguished with water, which is more blatant nonsense. Even the most-inept stoker would have known that throwing water into a glowing furnace would irreparably damage its refractory masonry, and even more-so, it cannot be believed that the head of the crematory would have given such an order. Furthermore, although Müller and Lulus were said to have been directly responsible for the alleged fire, Stark did not kill them, but instead four other, uninvolved inmates (Kraus-Kulka Statement) or only three (Müller 1979b, p. 18), namely: “Neumann, Goldschmidt and Filip Weiss “ (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20579).

Regarding the crematorium chimney, Müller initially had scanty and confused knowledge:

“In the summer of 1943, the furnaces and chimneys at the Auschwitz crematorium caught fire. Nazi engineers renovated them, but three months later the same thing happened again.” (Kraus-Kulka Statement)

In his book, however, he linked this event to the alleged fire (Müller 1979b, p. 40):

“Prisoner bricklayers replaced the round chimney which had been destroyed during the crematorium blaze by a tall new square chimney.”

Then he adds (ibid., p. 47):

“The continuous operation of the crematorium and, most of all, the overloading of the ovens – an aspect not taken into account during their construction –led to the crumbling of the fire-bricks of the inner lining, so that there was a danger of the chimney collapsing. Therefore, in the summer of 1942 a new square chimney with a double lining of fire-bricks was added. However, operations in the crematorium continued without interruption while this work was carried out.

A team of about thirty was building the new chimney, the majority of them Jewish prisoners.”

Here Müller either attributes two different causes to the same event, or he speaks of the chimneys having been rebuilt twice, or he refers to two different chimneys. The first hypothesis involves an evident contradiction, the second is historically wrong, and the third architecturally false, as that crematorium had only one chimney. I briefly summarize the actual events, which I described at length in another study,[13] but I state right up front that neither the crematorium, nor the furnaces, nor the crematorium chimney ever were on fire.

Between 14 and 15 May 1942 a repair was made to the “Kaminunterkanal,” the smoke duct that connected the three furnaces to the chimney, with the replacement of 50 refractory bricks.

On May 30, 1942, SS Oberscharführer Josef Pollok, in his capacity as the Auschwitz Camp’s building inspector, informed the head of the Auschwitz Central Construction Office, SS Hauptsturmführer Karl Bischoff, that the chimney framing (Kamineinband) had come undone, and that cracks had opened up in the masonry, which was partly due to overheating of the chimney. On June 1, Bischoff consequently prohibited the use of the chimney, thus effectively shutting down the crematorium, and at the same time reported to SS Brigadeführer Hans Kammler, head of Office Group C of the WVHA about this. The next day, Kammler issued an order for the chimney’s immediate reconstruction. The new chimney was built by 688 inmates (and not by “about thirty”) between June 12 and August 8. The old chimney was demolished after July 6.

Müller’s claim that the crematorium remained in operation during these construction works is afactual, because it was necessary to build two new smoke ducts: one 12.20 m long, which connected Furnaces 1 and 2 to the new chimney, the other 7.37 m long for Furnace 3. In July, deliveries of coke to the crematorium fell drastically. After a delivery of five tons on the 18th, the next delivery was made only on August 10th,[14] so the crematorium was certainly inactive for about twenty days, from July 20 to August 9.

Müller claimed that he worked at the crematorium until it closed, so he should have known these facts well. Instead, he told simple confabulations clearly based on second-hand information.

Later in his book, Müller returns once more to this chimney event, writing (Müller 1979b, p. 49):

“The building works department[15] of the SS had expected that, once the new square chimney was built, operations would run smoothly and without a hitch. However, it turned out quite soon that this new chimney could not cope with the work-load: while it was in use, lining bricks kept coming loose, blocking the flue. It was no longer possible to ‘dispatch’ the transports of Jews which continued to arrive as before without constantly recurring technical trouble. Therefore, in the autumn of 1942 operations had to be restricted.” (My emphasis)

In reality, however, the crematorium was immediately put back into operation at full capacity before fully curing the new chimney’s mortar, which was subsequently damaged by the rapid evaporation of the water still contained in it, causing new cracks to form, as Bischoff wrote to the camp commandant on August 13, 1942 with reference to his conversation with SS Hauptsturmführer Robert Mulka the day before.[16]

The relevant documentation does not contain the slightest reference to the cremation of corpses of gassing victims. Hence, the correlation claimed by Müller between the new damage to the chimney and the alleged gassings is purely imaginary. The scenario he presented is also in direct contradiction to that presented by French orthodox historian Jean-Claude Pressac (Pressac 1993, pp. 35):

“Since each gassing necessitated the complete isolation of the crematorium area, which disrupted the camp’s activity, and because gassings were unfeasible when work was in progress, it was decided at the end of April [1942] to transfer this type of activity to Birkenau.” (Emphases added)

In other words, the current orthodox narrative has it that no gassing took place anymore inside the Main Camp’s crematorium when Müller started working there.

Mass Graves at Birkenau (1942)

As a result of the alleged crematorium fire, Müller claims that the corpses not yet cremated were brought to Birkenau on trucks, but he provides contradictory data on both the number of corpses and the number of trucks used. In his first statement he claimed that “We loaded the remaining corpses onto three lorries” (Kraus-Kulka Statement), but one year later, he declared:

“On Aumeier ‘s initiative, two trucks were taken that same evening, at midnight, and the rest of the corpses, about 800, were loaded onto the trucks, and brought to the vicinity of Birkenau.” (Krakow Statement)

During his testimony at the Frankfurt Trial, Müller stated (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20480):

“It may have been 400 or 500 corpses, because (some) were burned in the crematorium before the fire.”

In his book, Müller writes merely (Müller 1979b, p. 20):

“Shortly before midnight we had finished loading the fourth and last truck.”

Finally, in his interview with Lanzmann he stated:

“And later in the evening, a few trucks came and we loaded the rest, maybe 300 corpses onto the trucks.” (Lanzmann 2010, p. 9)

Hence, there were either 800, 400-500 or 300 corpses to be hauled with either two, three or four trucks. If we follow Müller, this trip, in which he participated as well, was done only once. If we take the numbers he volunteered while testifying during the Krakow Trial, then we are to believe that two trucks carried 800 corpses, hence 400 each. Even if we assume with Robert Jan van Pelt that the bodies weighed 60 kg on average (van Pelt, pp. 470, 472), each truck would have carried a load of 24 tons, but the camp documentation shows that the trucks in the camp’s motor pool could carry a maximum load of 5 tons (see Mattogno 2015a, p. 55).

The second time Müller returned to the pit “on a fire engine” (Kraus-Kulka Statement), with a “fire engine” (Krakow Statement), with a “fire-brigade car” (Feuerwehrauto; Fritz Bauer…, p. 20483), which are all similar terms, but in his book, he claims to have been riding in an ambulance (Müller 1979b, p. 24), which is quite a different thing.

The story of the mass grave is completely unlikely and contrary to any organizational logic: in the middle of the night, the corpses would have been transported to Birkenau and thrown into a pit that had filled with water due to the high groundwater level, only to return the next day in order to pump the water out of the pit with a fire-brigade vehicle, to recover the corpses and pile them up “to make room for more,” and finally to cover them “with chlorine and earth” (Kraus-Kulka Statement). These operations would also have been useless, because “ground-water had seeped through into the pit” (Müller 1979b, p. 21), and after pumping it out, the pit would have filled up again, submerging the corpses again. Only a lunatic would have given such orders.

“Gassings,” the “Gas Chambers” and Zyklon B

On the first day Müller was taken to the supposed gas chamber of the Main Camp’s crematorium – on May 2 or 24, 1942 – he found “the first gassed Slovakian transport” (Krakow Statement). However, Danuta Czech ‘s Auschwitz Chronicle dates this alleged event to July 4, 1942, and the transport is not said to have been gassed in the crematorium, but in the Birkenau bunkers! (Czech 1990, pp. 191f.)

In his testimony during the Auschwitz Trial, Müller added 100 Soviet prisoners of war to the presumed gassing victims (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20470), but even for Czech this is pure fantasy. He specified that the deportees “died on their feet” (“im Stehen starben”; ibid., p. 20472[17]) and, incredibly, not even the defense lawyers contested such nonsense.

Having joined the “Fischl-Kommando” made up of seven inmates, Müller’s task consisted initially in undressing the corpses, who evidently had not undressed before being gassed and had even brought their luggage into the gas chamber (as Müller saw “suitcases” and “packages” among the corpses; ibid., p. 20470). The senselessness of this claim, which is in striking contradiction to the orthodox narrative, becomes palpable in the witness’s explanations. On “June [června] 17th, or 18th, 1942” – as Müller recounts in the Kraus-Kulka Statement – Himmler presumably inspected the crematorium during his visit to Auschwitz (which took place on July 17 and 18), and saw the clothes and linen of the gassing victims in the gas chamber:

“At the sight of these blood-stained garments, he turned to our SS chiefs in great surprise and asked why they were in this state. Dissatisfied with the answer he was given, he flew into a rage and thundered: ‘We need the clothing of these accursed dogs for our German people! It’s a waste to gas people in their clothes!’

After this the gas chambers were converted into mock bathrooms with water-pipes and taps, and the people had to undress before they went to their death [were gassed].”

Hence, according to this legend,[18] the practice of stripping the victims before gassing them would have been introduced no earlier than July 17, 1942!

It follows that, after ten months of alleged homicidal gassings,[19] the SS at Auschwitz had still not figured out that it was easier to have the victims undress themselves before gassing them rather than to remove the clothes from corpses. According to witness Walter Petzold, this “fatal mistake” (“verhängnisvollen Fehler”) was committed by the SS only on the occasion of the mythical first homicidal gassing in the basement of Block 11 of the Main Camp ten months earlier.[20] One might expect that they had learned their lesson by the time Müller started working in the Main Camp’s crematorium.

When writing his book in 1978/79, Müller probably no longer remembered the previous nonsense and asserted that “Today this new procedure was to be tried out for the first time” in the crematorium courtyard, where “today” refers to the arrival of a transport of Polish Jews from the Sosnowice Ghetto (Müller 1979b, pp. 31f.). Müller gives no date, but a few pages later he adds that, after a rest of three days (ibid., p. 35), another transport with several hundred Polish Jews arrived who were all destined for extermination (ibid., pp. 35f.), and he specifies (ibid., p. 39):

“Afterwards this technique was used as a reliable method for the mass extermination of human beings without bloodshed, and it began to assume monstrous proportions. From the end of May 1942 one transport after another vanished in this way into the crematorium of Auschwitz.”

Hence, Müller not only contradicts the orthodox Auschwitz narrative, but also himself.

According to Müller, the cremation activity resumed several days after the alleged fire (ibid., p. 30), therefore in the first ten days of May (or in early June, if we use Müller’s other timeline), with the arrival of the transport of Jews from the Sosnowice Ghetto mentioned earlier (ibid., p. 32); on that occasion, 600 people were allegedly gassed in the crematorium’s morgue that is said to have been repurposed as a homicidal gas chamber (ibid., p. 33).

According to the Auschwitz Chronicle, the first Jewish transport from Sosnowice arrived in Auschwitz on May 12, and it was allegedly gassed entirely in “Bunker 1” at Birkenau (Czech 1990, p. 166), not at all in the crematorium. However, there is no document in this regard. Czech’s source is in fact a simple, somewhat-vague statement in a 1946 book:

“On May 12 [1942], the day of the first evacuation, the process of the systematic operation of total extermination of the Jews of Sosnowice began, which ended in January 1944.” (Szternfinkiel, p. 34)

How Czech deduced from this meager “information” that a Jewish transport actually departed from the Sosnowice Ghetto on that day, that it contained 1,500 Jews, that it arrived in Auschwitz on that same day, and that all its claimed deportees were gassed without exception, and in “Bunker 1” to boot, remains a complete and utter mystery.

At this point, Müller runs into another contradiction. During the Frankfurt Trial, he stated that the members of the Birkenau “Sonderkommando” called the then SS Oberscharführer Wilhelm Boger, one of the defendants on trial, “Malech Hamuwes” – angel of death – because he brought the transport announcement:

“The ‘Sonderkommando’ said about Boger: ‘Malech Hamuwes is coming.’ That means: ‘Death is coming.’ In the crematorium, Boger was called: ‘Malech Hamuwes is coming.’ That means in Yiddish: ‘Death is coming.’ When Boger comes, you don’t say: ‘It is Boger,’ but you say: ‘Malech Hamuwes is coming.’” (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20514f.)

During the interview with Lanzmann, however, this nickname appears in a completely different context. When the transport from Sosnowice arrived, consisting of 250-300 people (down from 600 in his book, although Czech insists there were 1,500 deportees), Müller heard the words of the deportees, such as “‘fachowitz’, which means ‘a skilled tradesman’. And then I could make out, ‘Malekenowis’ [Malech Hamuwes], that’s Yiddish for ‘the angel of death’” (Lanzmann 2010, p. 19).

During the Frankfurt Trial, Müller further stated that he had witnessed gassings “many, many times” (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20498), but he only pointed to the three mentioned above. For the rest, he limited himself to generic statements:

“Gassings happened all the time. Back then – I’m talking about May, June 1942 – people were gassed either before roll call or in the evening after roll call […]” (ibid.)

“Gassings occurred either in the evening after roll call or early before roll call, so that (at) eight o’clock, after eight o’clock, only the clothes (were there). About three times in a week people were gassed like that.” (ibid., p. 20499f.)

“It goes on like this for six weeks, as I see Stark doing this job. He must [have sent] at least – at least, I say – 10,000, 11,000 people into the gas.” (ibid., p. 20504)

“At least 10,000, 11,000 were gassed, at least from what I have seen with my eyes from one, two meters away.” (ibid., p. 20505)

To these 10,000 to 11,000 gassing victims must be added those alleged shot:

“In 1942, during the six weeks I was there, Stark shot people there, too. Those were the small transports of Jews that were picked up at the bunkers, which I have already mentioned. 80, 100, 120, 60 once, yes.” (ibid., p. 20537)

“Moreover, two are standing there who have worked with him in the gas chamber, the SS members. Yes, the Rottenführer from the Political Department and the Unterscharführer. Because one did not (gas) in the Auschwitz crematorium, if 80 or 100 people arrive; they were not gassed in this gas chamber. Only more, 500, 600, 700 or 300, like that. And back then, when more than 60, 70, 80 or 100 people arrived, the Unterscharführer shot with him together.” (ibid., p. 20538)

In his book, Müller wrote (Müller 1979b, p. 44):

“If a transport of less than 200 people arrived for liquidation then, as a rule, they were killed not by gassing but by a bullet through the base of the skull.”

Regarding the shootings, Müller asserted that Stark and Unterscharführer Klaus had killed together “at least 2,000” people, and that the tasks were divided as follows between the two (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20587):

“Klaus only shot when (transports with) 80 or 100 (people) came. But often transports arrived with only 50 or 60 people. Then Stark shoots.”

The total number of murdered victims allegedly seen by Müller within six weeks therefore amounts to 12,000-13,000. The alleged 10,000-11,000 gassing victims should correspond to about 20 transports of 500-600 people each, but as noted earlier, the witness only mentions the first three. Where did the others come from?

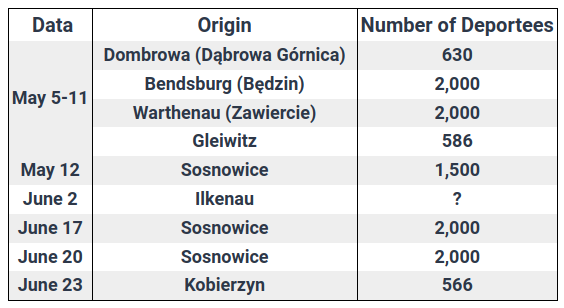

Czech ‘s Chronicle directly contradicts these statements, because for the months of May and June 1942, it records various transports destined for gassing, but they are claimed to have been sent to the Birkenau “bunkers” for extermination, and only one of these claimed transports had such a small number of deportees. I list the transports claimed by Czech in the following table:

To top it off, all of these transports are completely invented, as I have demonstrated elsewhere (Mattogno 2016d, pp. 35f.).

As mentioned, the Main Camp’s crematorium was supposedly equipped with a “gas chamber,” yet during his testimony at the Auschwitz Trial, Müller was rather evasive and even enigmatic, merely stating:

“The gas chamber was not as big as I will then describe the gas chambers at Birkenau. No window in it, just above, below a fan and light.” (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20493)

Speaking of the alleged victims, the witness specified:

“No, they weren’t shot. They were gassed. But when I got there the first time, I didn’t know. Afterwards we saw that there was a hall below. There was a large fan below that was turned on. Down there, there were still such green crystals. And there were no people a meter (away) from them.” (Fritz Bauer…, p. 20471)

Where was this fan located? Below what? No one at the hearing asked the witness these obvious questions. In the book, he talked about it again, but without making the matter any clearer either (Müller 1979b, p. 13):

“I noticed that there were some small greenish-blue crystals lying on the concrete floor at the back of the room. They were scattered beneath an opening in the ceiling. A large fan was installed up there, its blades humming as they revolved.”

The side view of the “Inventory Plan of Building No. 47a, BW 11. Crematorium” mentioned earlier shows a large curved tube above the roof of the morgue, the alleged gas chamber. As I explained in detail in another study, it could only contain an air-intake fan, because for extracting the air from that morgue, a separate duct was planned connecting the room to one of the smoke ducts in the adjacent furnace room, which sucked out air from the morgue due to the low pressure created in the smoke duct by the chimney’s draft, possibly enhanced by the forced-draft system installed next to the chimney (Mattogno 2016c, pp. 83-87).

In order to function, an air-extraction fan as suggested by Müller would have required a way of letting fresh air into the room, either by way of a similar ventilation fan, or by opening of one of the two (or both) of the morgue’s doors,[21] with the latter way risking contamination of the entire building with hydrogen-cyanide fumes.

The witness had never previously expressed himself clearly on the alleged introduction openings of the Zyklon B piercing the reinforced concrete roof of the crematorium. It was only in 1979 that he indicated their number, asserting that they were “six camouflaged openings” fitted with covers (Müller 1979b, p. 38). But this is notoriously in contrast to the official number of openings allegedly restored in the room by the Auschwitz Museum: four (Mattogno 2016c, Doc. 23, p. 133).

The description of Zyklon B as “green crystals,” which in the book became “green-blue crystals” (Müller 1979b, p. 38) and even “purple grains” (only in the German edition, 1979a, p. 183; excised from the English translation, 1979b, p. 115), and in the interview with Lanzmann “blue-purple crystals” (2010, p. 7), was a fable already en vogue immediately after the war that the witness undoubtedly drew from Rudolf Höss ‘s “confessions,” for whom Zyklon B was precisely “a crystal-like substance,” “a crystallized Prussic acid” (Mattogno 2020b, pp. 44, 66). As for the color of Zyklon B’s inert carrier material, Müller makes another mistake. At the time, as it appears from the “Guidelines for the Use of Prussic Acid (Zyklon) for Destruction of Vermin (Disinfestation)” issued by the Health Authority of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in Prague (NI-9912), among other sources, this carrier material was made of either “a granular red-brown material (‘Diagriess’)” of diatomaceous earth, “or small blue cubes (‘Erco’)” of gypsum. Hence, what could have been mistaken for “crystals” with some imagination, were actually either grains of diatomaceous earth, although it had a red-brown color, or of gypsum granules which were indeed bluish (neither green, green-blue, nor blue-violet), but it would have been absurd to call them “crystals.”

Given its dangerous nature, this carrier material was removed immediately from the disinfestation gas chambers as soon as the residual gas test (Gasrestprobe) was negative and allowed access to the room for specially trained personnel equipped with gas masks (see Mattogno 2004b). This would have applied also to any homicidal gassings. Müller, on the other hand, apparently performed his gas test with his sense of smell and taste, because he wrote in his book (Müller 1979a, p. 185):

“Because the gas was neither odor- nor tasteless. It smelled of burning dry alcohol and produced a sweet taste on the lips.”

In the English edition, this was condensed to this brief partial sentence (Müller 1979b, p. 116):

“[…] because the gas smelled of burning metaldehyde and had a sickly-sweet taste.”

So, he had inhaled it and tasted it without wearing a gas mask! This fable had already been uttered by Dragon:[22]

“After opening, it was very hot in the room, and there was gas; it was suffocating, and it was sweet and pleasant in the mouth.”

It is therefore clear that Müller has never seen any Zyklon B in any “gas chamber,” despite his assurances to the contrary.

“Gassings” in the Crematorium: Müller versus Höss, Jankowski, Piper and Pressac

During the Polish trial staged against Rudolf Höss in Warsaw (March 11-29, 1947), the former Auschwitz commandant made two important statements about the alleged gassings in the crematorium of the Main Camp – in fact, there was only one such gassing according to him (Mattogno 2020b, pp. 214, 165):

“Women were never gassed in Crematorium I. Exclusively those Russian prisoners were gassed there.” (10th Hearing, March 21, 1947)

“After the first gassing in Block No. 11 – this was the prison building – the gassings were transferred to the old crematorium, in the so-called morgue. The gassing was done this way: holes were made through the concrete ceiling, and the gas – it was a crystalline mass – was poured through these holes into the room. I only remember one transport. 900 prisoners of war were gassed in this way. From then on, the gassing was carried out outside the camp, in Bunker 1.” (11th Hearing, March 22, 1947)

Therefore, 900 Russian prisoners of war were gassed in the crematorium, after which the gassings were carried out in the “bunkers” of Birkenau. In other words, no Jewish transport was ever gassed in the morgue of the old crematorium. It should be emphasized that Czech ‘s Auschwitz Chronicle, and consequently the historiography of the Auschwitz Museum, is based precisely on these statements by the former camp commandant.

Müller first mentioned Jankowski in the deposition at the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial (97th hearing), where he mistakenly referred to him as “Samuel.” The circumstances of the encounter are as follows: after the transport of the corpses to the mass grave at Birkenau, the crematorium Kommando was taken back to a cell of Block 11. On that occasion, the door was opened and three other inmates were put into that cell, including Jankowski, but Müller said nothing about his activity at the crematorium. As will be seen, the reason for this is easily understood. He merely reported that he had been transferred to Birkenau with Jankowski (98th hearing). In his book, Müller mentions Jankowski only three times in insignificant contexts.[23]

For his part, Jankowski, in the deposition of April 16, 1945, did not mention Müller at all, and in his 1985 report, hence after Müller’s book had appeared, he mentioned a “Müller from Slovakia” only briefly as one of the six Jews who had worked at the crematorium.[24]

It ought to be kept in mind that Müller claimed that in the crematorium there was a real “gas chamber” complete with a fan and Zyklon-B-introduction openings at least since May 1942. Furthermore, he declared with reference to this “death factory” (Müller 1979b, p. 51):

“Tens of thousands of Jews from Upper Silesia, Slovakia, France, Holland, Yugoslavia and the ghettos of Theresienstadt, Ciechanow and Grodno had been put to death and cremated there […]”

According to Danuta Czech, however, these transports were all gassed in the Birkenau “bunkers”! Contradicting himself, Müller also wrote (ibid., p. 49):

“From the start this small ‘death workshop’, into whose gas chamber more than 700 people could be crammed, served to relieve the two extermination centres at Birkenau. Known as Bunker 1 and 2 these were two whitewashed farmhouses with thatched roofs, all that remained of the village of Brzezinka.”

The transports listed in the table of Subchapter 2.5. (see p. 195) are all those that are said to have arrived at Auschwitz in the months of May and June 1942. If we assume that the transport from Ilkenau contained 1,500 people, just like the previous one from Sosnowice, then this means that for Müller basically all, or almost all, the transports arriving at Auschwitz would have been gassed in the crematorium: about 12,800 people. Hence, it would have been the “bunkers” (to be precise only “Bunker 1”) that would have served “to relieve” the Main Camp’s crematorium!

Finally, in the book, which should represent the final and most-authoritative version of his contradictory statements, Müller claimed that he remained in the crematorium until July 1943, so he must have known everything that had happened there.

In 1947, Jankowski testified the following instead:[25]

“I declare that at the time, it was the end of 1942, there were still no gas chambers in Oświęcim [Auschwitz]. The only gassing of that period known to me took place in November or December 1942. At that time, 390 people were gassed, only Jews of various nationalities, employed in the Sonderkommando of Birkenau. This gassing was then carried out in the Leichenhalle [morgue]. I heard from people employed in the crematorium that even before this gassing some gassings had been carried out in this same Leichenhalle and in other rooms of the crematorium [i różnych ubikacjach krematorium].”

In 1985, the witness stated:[24]

“At the crematorium, the corpses of inmates who died in the camp were cremated, the corpses of those killed in the gas chamber [komora gazowa] – I remember the gassing of about 400 members of the Birkenau Sonderkommando who had been deployed in the open-air cremation of the corpses, and of some other gassing victims.”

Hence, 38 years later, the morgue had turned into a real “gas chamber,” a function that it did not have specifically before, since gassings had also taken place “in other rooms of the crematorium,” but of these “other gassing victims,” Jankowski could not say anything specific, so in this witness’s “knowledge,” the gassing of the approximately 400 inmates of the “Sonderkommando” remained the only “real” one.

Regarding this “Sonderkommando,” Müller specified in the deposition at the Frankfurt Trial (98th hearing) that it was made up of Slovak Jews who were preparing to escape, but were betrayed by an inmate and that “this ‘Sonderkommando’ was gassed at the end of 1942 or at the beginning of 1943.” The event took place in Auschwitz, and he learned about it in Birkenau: “I heard it in Birkenau […]. I heard it at the Birkenau camp” (Fritz Bauer…, pp. 20762f.).

In contradiction to this, Müller wrote in his book that he actually witnessed the alleged gassing (Müller 1979b, p. 50):

“In mid-December 1942 all who belonged to this Sonderkommando were gassed and cremated. On removing their bodies from the gas chamber we found on some of them scraps of paper with notes scribbled on them to the effect that their plan to escape had been betrayed by certain barrack orderlies.”

These are not the only contradictions between the two “eyewitnesses.” Regarding the crematorium’s “gas chamber,” Müller stated that it had “six camouflaged openings,” while Jankowski stated:[26]

“This large hall had no windows, it only had two valves in the ceiling and electric lighting, as well as an entrance door from the corridor and another leading to the furnaces. This hall was called Leichenhalle (corpse hall). It served as a morgue and at the same time for ‘slaughters’, that is, inmates were shot there.”

In his affidavit of October 3, 1980, the witness stated (Pressac 1989, p. 124; see Chapter 9):

“It is at Auschwitz that I saw for the first time a gassing in the Leichenhalle. This room had no windows, but there were ventilators in the ceiling. The two thick wooden doors of the room, one in the side wall, the other in the end wall, had been made gas tight. The room was lit by electricity.”

Finally in 1985, he asserted:[27]

“The gas chamber inside was painted white, on the ceiling, to the best of my memory, there were two gas-feeding holes [były dwa otwory do wsypywania gazu]; there were no fake showers; I don’t remember a fan.”

Jankowski ‘s statements are therefore contradictory and in direct conflict with those of Müller, also regarding the absence of fake showers, which for Müller were installed after Himmler ‘s visit to Auschwitz.

Another contradiction concerns the operation and cremation capacity of the furnaces. For Müller, three corpses could be cremated simultaneously in a muffle within 20 minutes; according to Jankowski, a muffle could hold up to twelve corpses, but only five were placed in them simultaneously, because this way they burned better.26 Jankowski did not say how long the cremation of such a batch took, which is even more-absurd than the one described by his colleague.

In 1985, Jankowski asserted:[24]

“In the crematorium, there were three furnaces, which each had two hearths. Three corpses were generally placed into each opening. Only at the end of the work [shift], 10-12 corpses were placed inside, which burned in our absence. The introduction of such a number of corpses was not easy, so the Kapos took care of it themselves. The corpses were crammed in by placing a special poker under their armpits. The cremation of a load of five corpses lasted about half an hour.”

The claim that five corpses placed in a single muffle could burn within half an hour is technical nonsense, and that 10-12 corpses could even be introduced into a single muffle is utter delusional nonsense.[28]

From what Jankowski said about the furnaces, it is also certain that he had a rather faulty idea of how they operated:[29]

“The corpses lay on the grates, under which coke was burning [pod którymi palił się koks].”

Rather than a cremation furnace, for him it was a barbecue grill!

When the officials of the Auschwitz Museum had two of the three original furnaces rebuilt in the Main Camp’s former crematorium after the war, they were undoubtedly inspired by this nonsense, since – as I will explain immediately – they forgot to reconstruct the two coke-burning gas generators in the rear part of each furnace, so that the hearth grates, which were originally located at the bottom of the gas-generator well, were installed beneath the muffle grates instead!

In 1985, Jankowski himself hinted at this, but in a somewhat confused way:[30]

“The currently reconstructed furnaces differ a little from the ones we had to operate, that is, the coke was poured into them from above through a special opening that was at floor level.”

In fact, the most-striking difference of this reconstruction compared to the original furnace is that the entire wall structure of the two gas generators is missing, a block attached to the rear part of the furnace measuring 2.5 (length) × 0.6 (width) × 1.4 (height) meters, with the upper surface being inclined. The double-leaf gas-generator loading-shaft door (Generatorfüllschachtverschlüsse) mentioned by Jankowski were arranged on this inclined surface. The gas-generator structure was accessed through a service shaft (Schacht) 0.95 meters deeper than the surrounding floor of the furnace room, so the two doors were located 0.45 meters above floor level,[31] hence not quite “at floor level.”

Regarding the cremation capacity of these furnaces, it is also worth mentioning the relevant statements by Henryk Tauber:[32]

“In Crematorium I, there were three furnaces with two muffles each, as I mentioned earlier. Each muffle could cremate five human corpses. Therefore, 30 human corpses could be cremated simultaneously in this crematorium. During the time I worked in the service squad of this crematorium, the cremation of such a load lasted an hour and a half.”

It follows that the three double-muffle furnaces of this crematorium had, at the same time, the phenomenal capacity of three corpses per muffle within 20 minutes, five within half an hour, and again five, but in an hour and a half!

In this context, it is worth underlining that Müller’s story is also in total conflict with Jean-Claude Pressac ‘s historical reconstruction. With reference to the Main Camp’s crematorium, he wrote in fact (1993, p. 34):

“The SS could only conduct gassings there from January 1942 until the date in May when the assembly of the third furnace was resumed, that is to say during four months. It is currently estimated that very few homicidal gassings took place in this crematorium, but that they were amplified because they were so impressive for the direct or indirect witnesses.”

As noted earlier, Pressac said the gassings were transferred to Birkenau “at the end of April” of 1942, so they had ceased even before Müller was assigned to the crematorium!

The Frankfurt Court did not take Müller’s deposition at the Main Camp’s crematorium too seriously, on which it ruled:

“The account of the witness Müller about the gassing of Slovak Jews is not very clear. As far as the court knows, gassing no longer occurred in the small crematorium, but in the farmhouses that had been adapted for this purpose.” (Langbein, p. 884)

A diplomatic way of saying that the witness was a perjurious liar.

Comments